What Colours To Use?

The mental images we have of seventeenth century dress are invariably of a dashing cavalier, wearing extravagant clothing and an ostentatious feather in a broad-brimmed hat; or a dour Puritan dressed in black and white. A heavily stylised, but very enduring set of images created by the Victorians. But what was the reality?

Some clothing from the time still exists, although this will, by the very nature of things, have belonged to rich owners. It has been suggested too, that due to interest in the civil wars, that these surviving garments have been fancydress-ified by the Victorians to achieve the romantic nature of dashing cavaliers and their ladies.

Some clothing from the time still exists, although this will, by the very nature of things, have belonged to rich owners. It has been suggested too, that due to interest in the civil wars, that these surviving garments have been fancydress-ified by the Victorians to achieve the romantic nature of dashing cavaliers and their ladies.

Thanks to rising temperatures the C17th and C18th graveyard at Spitsbergen is giving up its inhabitants - whalers buried in their clothes. Many of these remarkable garments are on display at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (they also have the fantastic Night Watch painting). If you can't just pop into Amsterdam you can see some high resolution pictures here.

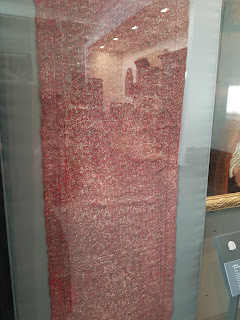

One example of surviving clothing items is a royalist officer's sash (which should, more correctly, be called a scarf) in the Victoria and Albert museum which has intricate silver/white embroidery.

Bear in mind that our dashing cavalier, in all his finery, might not be particularly accurate. On the 9th of June 1643, Charles issued a proclamation 'against the waste and excess in apparel':

One example of surviving clothing items is a royalist officer's sash (which should, more correctly, be called a scarf) in the Victoria and Albert museum which has intricate silver/white embroidery.

Bear in mind that our dashing cavalier, in all his finery, might not be particularly accurate. On the 9th of June 1643, Charles issued a proclamation 'against the waste and excess in apparel':

'His Majesty taking into His consideration the great vanity and excess in Apparel, now in use in several sorts and degrees of people, and the great waste and consumption of gold and silver therin, (at all times very unfit, and hurtful to particular persons, and to the Kingdom, but in these times most insufferable)...'This proclamation then lists a whole host of banned items (ribbons, lace embroidery, fringe, extravagant fasteners ad buttons, the use of gold and silver, pearls) that can not be used on clothing or horse furniture.

A quick trawl around the National Gallery throws up a number of useful paintings. There is a gallery of Van Dyck's, showing portraits of Charles’s inner circle: the colours on display clearly shout 'wealth' so are very unlikely to have been worn by the rank and file. Van Dyck's portrait of the two Stuart brothers stands out as the archetypal dashing cavalier trope.

So what colour cloth was used to make clothing for the common man? Fortunately we can draw on the research done by the many re-enactors of the period. Google will provide a number of suitable sites, two of the best that I've found are:

Rosalie Gilbert's site

Nicole Kipar's site

Another excellent picture resource is Goodwyfe's blog 1640s Picture Book, which despite the nom de plume is actually run and written by re-enactor and TV cameraman Ian Dicker. Oodles of pictures of clothing and items from the 1640s.

Paintings were generally of the well to do rather than common folk, so period images are skewed towards the richer social classes. I have read that many of the Dutch paintings of the time can be considered fairly representative of dress in the British Isles, plus we can also consider the 'sadd colours' used by the pilgrims to the Americas. (Sadd meaning serious rather than sad.) These colours were deliberately subdued, and consisted of natural earthy country colours. Think traditional tweed cloth colours: so lots of greys, browns, greens, tawny oranges, earthy yellows (as opposed to bright lemony yellows) as well as russet red, madder red, heather purple.

Dyes were plant based so will probably have faded fairly quickly, although textile researchers have found natural ways of fixing madder red using urine.

'Woman and five children' by the Le Nain brothers (1642) shows these subdued countryside colours with madder red and dark blue.

Another useful painting is Velázquez's "Phillip IV hunting boar" (1632-7), whilst Spanish the colours of the servants and retinue gives a good feel for the effect I aim to achieve. Lots of browns, greys, greens so again earthy colours, with a smattering of madder red, blues and black.

Then things could get a little confusing. The term "orange" is a fairly new concept in C17th England. Think of red deer, red heads, red squirrels etc - orange was effectively a shade of red. The more cosmopolitan areas, think London and Oxford, as well as the country's ports might well be familiar with the fruit orange, so the colour orange might be more widely used. The Orange Regiment of the London Trained Bands being one example. Travel to the quieter backwaters and oranges could well be an unknown mythical fruit.

So what colour cloth was used to make clothing for the common man? Fortunately we can draw on the research done by the many re-enactors of the period. Google will provide a number of suitable sites, two of the best that I've found are:

Rosalie Gilbert's site

Nicole Kipar's site

Another excellent picture resource is Goodwyfe's blog 1640s Picture Book, which despite the nom de plume is actually run and written by re-enactor and TV cameraman Ian Dicker. Oodles of pictures of clothing and items from the 1640s.

Paintings were generally of the well to do rather than common folk, so period images are skewed towards the richer social classes. I have read that many of the Dutch paintings of the time can be considered fairly representative of dress in the British Isles, plus we can also consider the 'sadd colours' used by the pilgrims to the Americas. (Sadd meaning serious rather than sad.) These colours were deliberately subdued, and consisted of natural earthy country colours. Think traditional tweed cloth colours: so lots of greys, browns, greens, tawny oranges, earthy yellows (as opposed to bright lemony yellows) as well as russet red, madder red, heather purple.

Dyes were plant based so will probably have faded fairly quickly, although textile researchers have found natural ways of fixing madder red using urine.

'Woman and five children' by the Le Nain brothers (1642) shows these subdued countryside colours with madder red and dark blue.

Another useful painting is Velázquez's "Phillip IV hunting boar" (1632-7), whilst Spanish the colours of the servants and retinue gives a good feel for the effect I aim to achieve. Lots of browns, greys, greens so again earthy colours, with a smattering of madder red, blues and black.

Then things could get a little confusing. The term "orange" is a fairly new concept in C17th England. Think of red deer, red heads, red squirrels etc - orange was effectively a shade of red. The more cosmopolitan areas, think London and Oxford, as well as the country's ports might well be familiar with the fruit orange, so the colour orange might be more widely used. The Orange Regiment of the London Trained Bands being one example. Travel to the quieter backwaters and oranges could well be an unknown mythical fruit.

Another 'colour' that might cause concern for the modern reader is 'puke', which was a colour somewhere between black and russet. Top tip: don't try and Google 'puke colour', as it will inevitably bring up various shades of green (pun intended btw).

Looking at my ECW paint palette there are lots of earthy named colours from Foundry such as granite, moss, quagmire, and peaty brown, which have been supplemented by a number of WWII colours such as British khaki, Russian brown. Of course madder red, and a number of dark blues have joined the colour range.

Whilst at Croperdy 375 I chatted to one of the ladies at the Sealed Knot living history camp (to whom I am indebted for her work), here are some pictures of wool that she dyed using plant based dyes that were available in seventeenth century Britain. I now consider it my colour chart! Admittedly, in the seventeenth century they dyed completed cloth rather than yarns, so there would be a slight difference, but it is an excellent colour palette to work from.

Black is problematic, I tend to use 'neat' black for commanders/gentry, but weathered black (RailMatch) for the rare use of black for the hoi polloi.

I've also become a fan of Foundry blackened barrel for armour, and buff coats look particularly lived in once washed in Citadel Agrax Earthshade.

Scots troops were invariably clothed in Hodden Grey - which isn't a specific shade of grey. Hodden grey was unbleached woollen cloth. The hardy sheep breeds bred had brown or grey white fleece, which gave variations in colour from the brown of Jacobs sheep through to light grey. My Scots soldiers are either Foundry arctic grey or granite, toned down with Citadel Nuln Oil.

For the total obsessive there are a number of volumes in the series "Clothes of the Common People in Elizabethan and Early Stuart England" which go in to very great detail about cloth types and colours.

See also my post on regimental coat colours.

Looking at my ECW paint palette there are lots of earthy named colours from Foundry such as granite, moss, quagmire, and peaty brown, which have been supplemented by a number of WWII colours such as British khaki, Russian brown. Of course madder red, and a number of dark blues have joined the colour range.

Whilst at Croperdy 375 I chatted to one of the ladies at the Sealed Knot living history camp (to whom I am indebted for her work), here are some pictures of wool that she dyed using plant based dyes that were available in seventeenth century Britain. I now consider it my colour chart! Admittedly, in the seventeenth century they dyed completed cloth rather than yarns, so there would be a slight difference, but it is an excellent colour palette to work from.

Update: I have recently tried to translate these colours into paint codes from Foundry and Coat d'Arms - see here

Black is problematic, I tend to use 'neat' black for commanders/gentry, but weathered black (RailMatch) for the rare use of black for the hoi polloi.

I've also become a fan of Foundry blackened barrel for armour, and buff coats look particularly lived in once washed in Citadel Agrax Earthshade.

Scots troops were invariably clothed in Hodden Grey - which isn't a specific shade of grey. Hodden grey was unbleached woollen cloth. The hardy sheep breeds bred had brown or grey white fleece, which gave variations in colour from the brown of Jacobs sheep through to light grey. My Scots soldiers are either Foundry arctic grey or granite, toned down with Citadel Nuln Oil.

For the total obsessive there are a number of volumes in the series "Clothes of the Common People in Elizabethan and Early Stuart England" which go in to very great detail about cloth types and colours.

See also my post on regimental coat colours.

If you enjoyed reading this, or any of the other posts, please consider supporting the blog.

Thanks.

Over the weekend I started work on my Confederate Irish. Given the restrictions on industry, I'm plumbed for natural colours, a core of 'hodden grey' as above with hints of traditional leine(sic) holdouts and the odd veteran in red or similar. All well and good except, bar the pikes, they look like American Confederates! I guess that's what happens when you are restricted to natural sources! ;-)

ReplyDeleteI imagine that that palette could be used for a number of armies across several millennia.

DeleteGood luck with the army

Just had an argument on Facebook (no, surely not???) over a photo of a set of AWI re-enactors depicting rebel militia - ie essentially folk in civilian dress. Citing stock inventories of Colonial haberdashers, I said I thought black hats were rare for civilians, due to the difficulty of dyeing material black, and more importantly keeping it black. The latter usually required several repeats of the dyeing process, which was why black, at least as a clothing colour, tended to be the province of the wealthy (senior clergy, etc). Failure to do this led the "black" to quickly fade, due to weather and use, to a dusty brown.

ReplyDeleteI have to say that 17th Century paintings of soldiers in the field show that black hats were rare at that time - almost entirely limited to the senior officers (see above) - and this remained the case until the early 18th Century. Does this agree with your findings?

Apologies - a bit of a rambling answer I'm afraid. I can't really help with the eighteenth century - no idea if dying processes had become cheaper (in particular black dyes). Certainly C17th black was a very aspirational colour to have, it meant you were wealthy. People who could afford it may have had just one or two items of black clothing that they wore on high days and holidays. For the vast majority of people black was out of the reach of their pockets. It also depends what hats are made from: not being very well up on hat construction in the Americas I would hazard a guess that hats are going to be made from whatever is easily available. In Britain wool is going to be the milliners material of choice; animal skins in the Americas? Also need to think about the demographic of settlers in the colonies too: those who settled will have had to have money to pay for their passage. I doubt very much that it was cheap, nor that vast numbers of poor people were making the crossing in order to practice religious freedoms. From a C17th stand point black is going to be seen on the well off and clergy, everybody else unlikely/probably not. Is our perception skewed by portraiture? Almost certainly, you've got to have disposable wealth to have a portrait painted of you. Much of this probably translates to the C18th in the colonies too.

DeleteThanks - that all makes perfect sense and pretty much agrees with what I know (or think I know - we could both be wrong, but let's go with "great minds think alike" until the opposite is proven!), based largely on reading blogs such as this one and some period clothing dissertations. This was pretty much the argument I presented but the respondent was having none of it. Something must have happened, around 1700, to render the production of black cocked hats (tricornes to the uninitiated) economically viable, to the point that each man got a new one each year. Perhaps it was the sheer numbers (combined with the lower level of dyeing)? Or the material (felt)?

DeleteOnce again, thank you for taking the trouble to answer a question that was not directly related to the Civil Wars.