Where to Start ECW Wargaming. Epically.

Today's post is geared squarely to newer readers of KeepYourPowderDry (who might, coincidentally, have just ordered boxes of new shiny things from Warlord Games); regular readers may find this post a useful virtual index page.

|

| Latest figure from the production line nears completion |

If Epic doesn't float your boat: you are going to have to decide on what size* figures you want to use; or more importantly work out a trade off on how much detail you can be bothered painting, or even if you can actually see the figures to paint them. Another consideration is what sort of games would you like to play and how much space do you have to play in?

Those of you wondering how to tweak, and supplement the look of your Epic figures might find parts 2b and 3b of my Which Figures? posts. Here are links to all of my Which Figures? posts:

Which Figures? - the original post, where I ruminate about what I want from figures, and what led me to choose Peter Pig.

Which Figures? What is Available - the state of play with current 'ECW' 15mm figure ranges; a continually updating look at what figures are available, and what is included/missing from ranges. No commentary on figure size or ruler action (that's down to parts 2a and 3a).

Which Figures? Part 2a: Size Matters: Foot - I show side by side comparisons of what is available in 15/18mm, with the obligatory ruler shots

Which Figures? Part 2b: True 15mm/Epic Compatibility: Foot - a more in depth look at smaller 15mm compatibility

Which Figures? Part 3a: Size Matters: Horses - I show side by side comparisons of what is available in 15/18mm (obligatory ruler content too)

Which Figures? Part 3b: True 15mm/Epic Compatibility: Horses - a more in depth look at smaller 15mm compatibility

.JPG) |

| Cromwell miniature, Ashmolean Museum Oxford |

Those of you who choose open-handed pikemen will also need to address the thorny issue (if you believe everything written on wargaming forums) of pike lengths.

Your next questions are which 'side' and which period of the wars you want to model? Early war Parliament or New Model Army? Royalist arms supply becoming slightly erratic as the Wars progress , when Parliament takes control of the ports, will give a more piece meal cobbled together look. The New Model Army, on the other hand, will start to look more uniform in appearance.

A little bit of nomenclature wouldn't go amiss if you are completely new to the period, this will help with the understanding that the series of Wars that blighted the British Isles are known by a range of names. What's In a Name?

Then of course we need to understand what the seventeenth century soldier understood by way of military organisational terminology. The early seventeenth century starts to formalise the way armies were organised and equipped, so we start seeing terms that we still use today. Somewhat unhelpfully, the terms don't necessarily mean what they do today.

Regiment: a regiment was an administrative unit, commanded by a colonel, who had had often earned that rank because they had deep pockets or a hereditary title. The Army Newly Modelled (the more accurate term for the New Model Army) started to challenge this notion (although in practice having a title and deep pockets did still smooth your way to the top of the food chain).

Regiments could be of foot, horse or dragoons. If you can tolerate my ramblings you will notice that I abbreviate these to RoF, RoH and RoD.

Colonels often held colonelcy of a number of regiments - if they were off being important somewhere else their place in the regiment, would be taken by a captain-lieutenant. There are a bewildering number of compound-name ranks in the Civil Wars, which have scant correlation to modern military ranks.

Regiments of foot were ideally 1000 men strong, divided into 10 companies of 100 men. In practice regiments would often be 6-700 strong. The London Trained Bands show their regiments at, or about, the 1000 man strength. The London Trained Bands (LTB) are often used by historians to illustrate their discussions and examples; their record keeping appears to be very complete, coupled with the evidence of Royalist spies, we know a lot about them.

Regiments functioned very differently to how they would in the Napoleonic Wars: each company was effectively independent, and would consist of musket and pike - which explains why regimental histories can show a regiment fighting in different parts of the country on the same day. Regiments that were part of the many field armies would brigade their companies together forming larger units (a bit more akin to how we think of a Napoleonic regiment fighting in battle).

There were a number of regiments of foot that we would describe as double strength, Newcastle fielded 14 companies of his regiment at Marston Moor (although each company might well have been understrength), and the Earl of Manchester is famous for having a double regiment (which might explain confusing coat issue problems). Field armies might also brigade companies from different regiments into one fighting unit: Frescheville's, Eyre's and Millward's regiments were brigaded together at Marston Moor giving a fighting strength of approximately 500 men. Three or four of these field brigaded regiments might be under the command of one officer, these organisations were known as battalia.

Regiments of dragoons and regiments of horse were subdivided into troops. Some regiments of horse also boasted troops of dragoons in their numbers.

The Hertfordshire Volunteer Trained Band Regiments consisted of foot, horse, dragoons and in one instance artillery pieces too.

There were also some smaller units, companies or troops, which existed outside of a regiment, they were usually raised for specific jobs. Often raised by a local member of the gentry for the purpose of garrisoning a grand house or strategic town, you do see them on larger battlefields and campaigns when circumstances necessitated. Expect to see companies of commanded shot, firelocks, and several independent troops of horse (particularly in Scotland).

Forlorn hope, a term that describes the potential survival chances of 'volunteers' tasked to do a job rather than being a specific job role. Usually used to describe a group of soldiers left to protect a retreat, or guard an indefensible position. It could also be used for a group tasked to place a petard under heavy fire.

Your next question is what types of soldiers were used during the Wars?

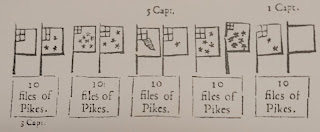

Infantry come in a variety of flavours. The most obvious being pikemen and musketeers. Those of you familiar with Streeter’s plan of Naseby will be aware that the pikemen form a central block when the regiment forms up. On either sides of the pike are wings, or sleeves, of musketeers – the ideal proportion being two musketeers to every pikeman. Musketeer sleeves would be the same depth of men as the pike block. Wargamers, myself included, are somewhat unhistorical by arranging musketeers in two rows but our pike in three or even four rows.

Pikemen started the Wars ideally wearing some form of helmet (the ubiquitously named pikeman’s pot), back and breastplates with tassets (effectively articulated, armoured ‘skirts’). As the Wars progressed soldiers behaved like soldiers and started to accidentally lose the heaviest pieces of kit – so the first to go are the tassets. Supply issues also mean some pikemen take the field with no armour whatsoever. (If you are tempted to become a complete anorak you'll want to know all about helmet development.)

Musketeers started the wars with whatever musket their officers could find – many had long, heavy pieces that require a musket stand to help hold and aim the musket when firing. Musket technology was improving and they started becoming lighter and shorter (and no longer require a rest). It is a bit of a wargamer fact™ that late war musketeers didn’t use rests. Rests appear to have been used throughout the period, although they do become less common as time progresses.

The Wars also see new formations of musketeers beginning to be utilised: these dispense with the pike block. Commanded shot is a general term for any unit of just musketeers. Firelocks were companies of musketeers who were equipped with firelock muskets – they no longer need a lit match to fire. As a result they were often, but not exclusively, used as guards for artillery trains.

.JPG) |

| Pikemans' and cuirassier armour, Littlecote Collection, Royal Armouries Leeds |

Cavalry start off the Wars wearing a whole host of armour. Many men took to the field wearing repurposed hand me down armour: helmets, cuirasses, and a few wore full suits of armour. These fully armoured cavalry are known as cuirassiers; there were a small number of troops of cuirassiers but they tend to be quite ‘rare’. There are a number of lifeguard troops who appear to have been equipped as cuirassiers (we can't be definite on this). Certainly during the 'excitement' of assembling troops at the outbreak of the First Civil War I don't think that is a too far a stretch of the imagination to have a handful of fully armoured men amongst a 'conventional' regiment of horse.

The physical weight of the armour, its restriction of movement, a shortage of horses strong enough to carry a fully armoured trooper, then throw into the mix the costs of both armour and horses all means that cuirassiers tend to be a short lived arm of the armies of the day.

The notable exception being the London Lobsters who were equipped as cuirassiers until they were driven over the escarpment edge at Roundway Down.

Lighter, more modern armoured cavalry are harquebusiers: so named after the arquebus long pistol/ short musket that they carried. Ideally wearing both a buff coat, and breast and back plates. Helmets would also be high on the kit list – in particular the three bar English pot.

Dragoons are a bit of an oddity: not the style of cavalry that we immediately think of, they were infantry who used horses to speed up, and extend their range, of mobility. C17th mobile infantry, if you will. Supposedly named after the style of musket first used by dragoons (dragons), the jury is out if this is actually the reason. They fought almost exclusively on foot, but as the Wars progressed, horses and weapons became harder to source for the Royalist cause, so you will often find dragoons becoming light cavalry and fighting as such. In such cases the swallow tails of their flags would be cut off, giving the look of a square cavalry guidon.

The Scots were a law unto themselves – taking the field as either conventional C17th soldiers, or as a rabble of men equipped with swords, axes, bows, spears, halberds. They also fielded lancers – lightly armed cavalry on small horses.

A basic understanding of Tactics probably wouldn't go amiss either: too great a subject to go into any depth here I'm afraid, and I haven't gotten around to writing anything about it (yet). The Osprey Pike and Shot Tactics 1590-1660 by Keith Roberts is excellent. If you want anything more in depth then you are going to have to go back to contemporary source material (sounds daunting), many drill manuals are published as facsimiles - one of the best known is Venn's Military & Maritime Discipline 1672: In Three Books... Military Observations on Tacticks put into Practice for the Exercise of Horse and ... Military Architecture... the Compleat Gunner.

To help with your research see:

ECW Wargaming Research: Getting Started - some suggested websites, and books to help you on your way.- Flags and Colours Part 3: Media and some sources for printed flags for your figures

|

| From Elton's The Compleat Body of the Art Military, showing Col Rainsborough's RoF 7th August 1647 |

- Coat Colours - an introduction

- Coat Colours Part 5: The Trained Bands and the wargamer fact™ about the London Trained Band Auxiliaries wearing blue coats.

- and finally Sashes*

|

| The Sealed Knot march out for a commemoration/recreation of the Battle of Nantwich |

- Painting Guide - Equipment and the Russeted Armour update.

- Painting Guide - Horses - it is pike and shot, you are going to be painting a lot of horses, here's how I paint horses quickly, and painlessly. Hopefully they look horse like. Look away if you actually know stuff about real horses.

And, finally if you want a little inspiration then the ECWtravelogue may well have somewhere close to you that has a Civil War connection for you to visit; if it is pouring down with rain and you'd rather have a sofa day then maybe the TV/movie reviews might have something for you to watch.

Postscript:

But, "what about Haythornthwaite?" I hear you ask... Haythornthwaite is a very inspiring book, the illustrations are beautiful (and have clearly been the inspiration for a number of figure ranges), but sadly the book is seriously flawed. It wasn't particularly 'accurate' when it was first published, and the years since then have been even unkinder. The illustrations in particular are reputed to have been 'made up as they went along', surviving artefacts confirm this allegation. So buy it (don't pay more than a fiver for it), flick through it with your favourite beverage and a good packet of biscuits for company, then put it to one side. (And in case you are wondering, the Ospreys aren't much better.)

* Wargames figures generally aren't scale figures in the same way that model kits are, figures are invariably a bit of a compromise on size, detail and method of manufacture. Sculptors, particularly with the smaller sized figures tend to make figures look 'right', rather than be anatomically correct. Be warned: mention scale on wargames forums and expect some individuals to be very rude explaining how you are wrong to use the word, and deserve to burn in hell for all eternity.

Comments

Post a Comment